An Invitation to Interact: ‘A New History of Western Art’ From Koenraad Jonckheere

A New History of Western Art – From Antiquity to the Present Day is not the dry tome of an academic, but of an enthusiastic storyteller who shows us how art continues to have new interpretations.

Koenraad Jonckheere

Koenraad Jonckheere© Stephan Vanfleteren

Art is the result of the most complicated of all human activities, and also the most enriching. It joins science with philosophy and activates our senses, our thoughts and our feelings. Yet many still consider art to be out of reach and incomprehensible. Koenraad Jonckheere, Professor of Art History at the University of Ghent, conceived A New History of Western Art as an exercise in writing an art history book for digital natives: ‘for those who are more familiar with augmented realities and immersive spaces created with the help of artificial intelligence than with the endless spectacle that art history has to offer, in both material and intellectual form.’

The author takes as his starting point not only his own admiration for art and artists, but also for those he has observed as they come into contact with art – sometimes a rather amusing experience. But alongside discussion of the wonderment of the viewer, there is also attention given to the “power” of the image which, for Jonckheere, holds no secrets: he specialises in iconoclasm and iconolatry, the contempt for and veneration of images.

What makes this art history different is not the story itself, but the way it is told

Jonckheere dedicates his book to his parents, who took their children to the terrace of the Café de la Paix in Paris to teach them how to observe. Next, they walked along the Avenue de l’Opéra to the Louvre, to learn how to see. This sets the structure and tone of this book. This is not the book of an academic – although the author certainly has the credentials – but the work of an enthusiastic storyteller who takes us along with him, not only to look but, even more importantly, to see, art. Because seeing is not merely perceiving, but also viewing, contemplating, discerning and judging.

What makes this art history different is not the story itself, but the way it is told. Or rather the way in which the same story is told five times, each version from a different starting point. This strategy creates a successive interest in art as a product, as an idea; as the combination between art and science, the connection between art and power/belief, and the relationship between form and content. ‘The purpose of this division is to show that works of art are intertwined with the historical dynamics in which they arise and the changing perspectives from which they are viewed.’

Kazimir Malevitsj, Black Square, 1915

Kazimir Malevitsj, Black Square, 1915© State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The thread that runs through all five divisions is Black Square by the Russian constructivist Kazimir Malevitsj. Each chapter begins with this mythic work, which the author successively claims is ‘an absolute masterpiece and high point of European art,’ ‘a sublime and concise synthesis of five centuries of art history,’ ‘the end of an era,’ and ‘the beginning of something completely new.’ He does not, however, regard this painting as a break from the past. ‘As one of the first non-figurative works of art in Western art history, it has affected the basic rules of mimetic art and helped create a path into a new way of thinking for artists.’

Jonckheere only briefly and sporadically touches upon what this new thought path of modern and contemporary artists entails. He does not give it the same systematic and analytical treatment as the 2,500 years of European art history that precede it. A New History of Western Art focuses on the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and on antiquities, given their importance for early Christian art, the Renaissance, the Baroque and Neoclassicism.

Illustrative of the appreciation of contemporary art is Jonckheere's observation that the intellectual discourse on art is centuries old

Illustrative of the appreciation of contemporary art is Jonckheere’s observation that the intellectual discourse on art is centuries old – from the Canon of Polycletus to the Suprematist Manifesto of Malevich – and that artists themselves define the basic principles and ground rules of their art, not only for the works themselves but also in the accompanying texts. By determining their own rules of the game, they immediately establish the criteria by which they want to be judged.

The different chapters teach us about specific techniques, the art market, the visual struggle, the evolution of the Renaissance idiom from an intellectual project to a political weapon and how artists played a central role in providing the visual language that was necessary in order to gain new insights into capturing reality (as in anatomy and cartography).

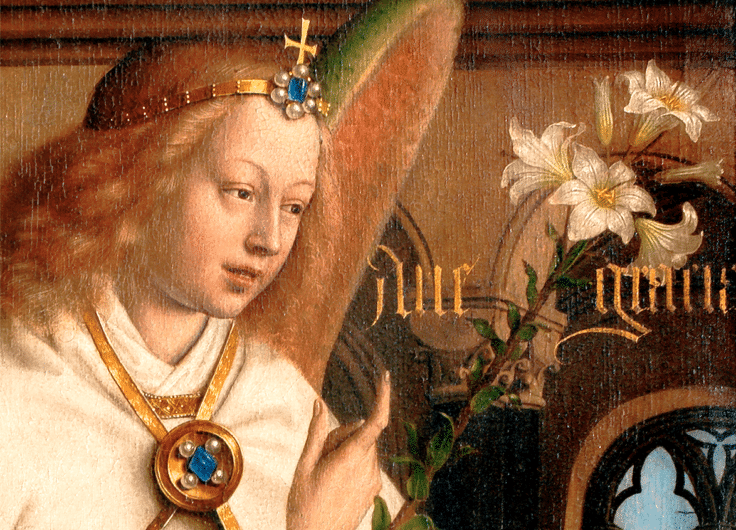

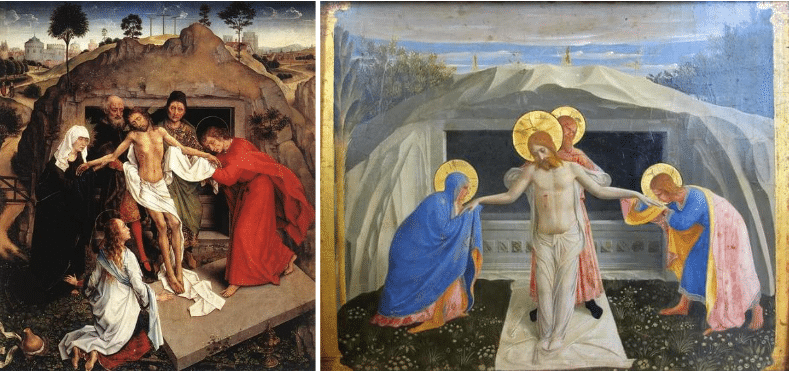

Rogier van der Weyden, The Entombment of Christ, ca. 1463–64 / Fra Angelico, The Entombment of Christ, ca. 1440

Rogier van der Weyden, The Entombment of Christ, ca. 1463–64 / Fra Angelico, The Entombment of Christ, ca. 1440© Wikimedia / Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence / © Wikimedia / Alte Pinakothek, München

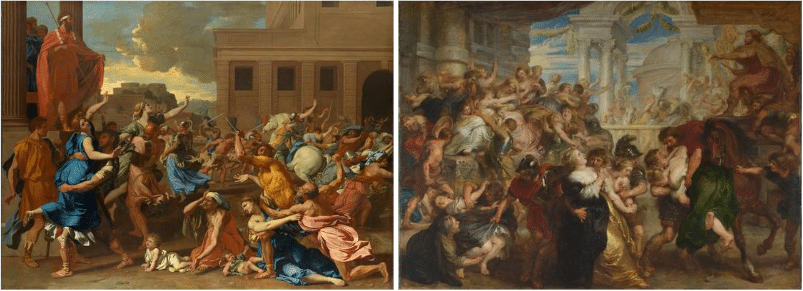

Because the book uses different “lenses” to encourage us to consider different aspects of art, we are able to look in a focused and attentive way. As a result, we “see” more and better. The visual material is used strategically. By juxtaposing The Entombment of Christ by Fra Angelico (circa 1440) and a similarly themed painting by Rogier van der Weyden (circa 1463-64), the difference between the idealised approach of the former and the realistic approach of the latter becomes immediately clear. The Abduction of the Sabine Women by Nicolas Poussin (1633-34) has grown out of a line drawing, while Rubens’ interpretation (1635-40) seems based on washes of colour.

Nicolas Poussin, The Abduction of the Sabine Women, 1633–34 / Peter Paul Rubens, The Abduction of the Sabine Women, 1635–40

Nicolas Poussin, The Abduction of the Sabine Women, 1633–34 / Peter Paul Rubens, The Abduction of the Sabine Women, 1635–40© Wikimedia/The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York / © Wikimedia/The National Gallery, London

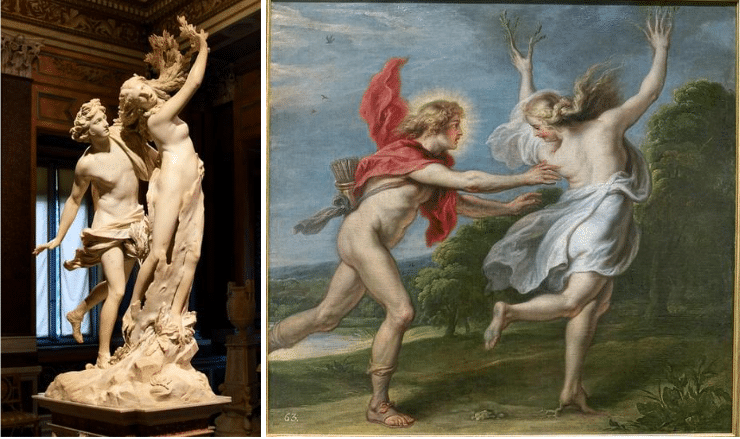

The way in which Bernini explores the pictorial possibilities of sculpture in his statue of Apollo and Daphne (1622-25) while Theodoor Van Thulden, one of Rubens’s collaborators, pursues sculptural effects in his slightly later painting on the same subject, is also enlightening and well-illustrated.

Gianlorenzo Bernini. Apollo and Daphne, 1622–25 / Theodoor van Thulden. Apollo and Daphne, 1636–38

Gianlorenzo Bernini. Apollo and Daphne, 1622–25 / Theodoor van Thulden. Apollo and Daphne, 1636–38© Wikimedia / Galleria Borghese, Rome / ©Wikimedia / Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

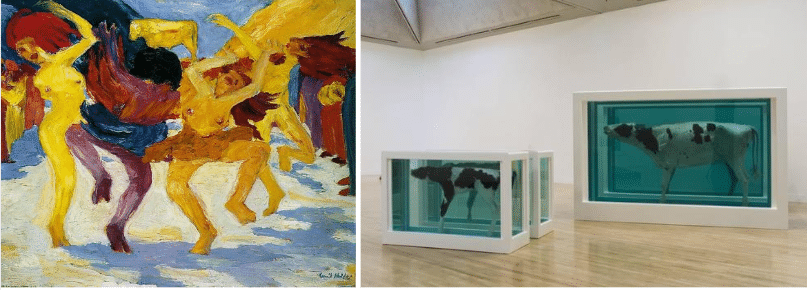

How a similar subject can, over centuries, take a different form and therefore be given a different interpretation is seen through Worship of the Golden Calf (Dans om het gouden kalf). In Lucas van Leyden’s version (ca. 1530) the idol disappears within the landscape and amongst the realistic details of the many human figures. Nicolas Poussin (1633), on the other hand, zooms in on the idol and, thus, on the idolatry, of the Israelites. The German expressionist Emil Nolde (1910) only has eyes for the ecstasy of the (half-)naked dancing girls. And Damien Hirst’s version of The Golden Calf (2008) (shown suspended in a vat of formaldehyde) holds up a mirror to his spectators, allowing them to circumnavigate his work like worshipers.

Lucas van Leyden, Worship of the Golden Calf, ca. 1530 / Nicolas Poussin, Adoration of the Golden Calf, 1633

Lucas van Leyden, Worship of the Golden Calf, ca. 1530 / Nicolas Poussin, Adoration of the Golden Calf, 1633© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam / © National Gallery, Londen

Emil Nolde, Dance Around the Golden Calf, 1910 / Damien Hirst, The Golden Calf, 2008

Emil Nolde, Dance Around the Golden Calf, 1910 / Damien Hirst, The Golden Calf, 2008© Wikimedia - Pinakothek der Moderne, München/ © Damien Hirst and Science Ltd. All rights reserved, DACS/Artimage 2020. Photo: Prudence Cuming Associates Ltd.

The final chapter, concerning the evolution of the relationship between form and content, reads more like a classic textbook on art history. And similar to those classic textbooks, it also ends in 1863 with Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe and the Salon des refusés, and with the message that art is no longer concerned with people and the world, but mainly with itself. Cézanne no longer paints landscapes but makes paintings.

The perception of art is a theme that runs throughout the entire book

The perception of art does not have its own chapter but is rather a theme that runs throughout the entire book. In the Epilogue, the author returns to the idea of perception when he writes about art as interaction. In his Introduction, he cites the famous opening sentence penned in Ernst Gombrich’s The Story of Art: ‘There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists’ There is, indeed, no art without artists, or without a public. The value of a work of art is determined by the various layers of meaning it is given first by the artist and over time by the individuals and communities that view it.

The book can also be read as an invitation to the reader/viewer to put the age-old uses into practice while adding yet another new layer of meaning to a piece of art – preferably through a physical confrontation. This is an activity that many museums have encouraged in recent years through the implementation of slow looking and visual thinking strategies.

In a note on art books, Gombrich distinguishes three different types in The Story of Art: books made for reading, books used as references and books to look at. Together with Hannibal Publishing, Koenraad Jonckheere has delivered all three for the price of one. A New History… is clearly written and pleasant to read. It isn’t really a reference work in the strictest sense of the word but a book, thanks to the extensive legends attached to the images and informative frame pieces (about Rubens’ atelier, fresco, mimesis, sketching, perspective, panels and canvas…), you can regularly return to and ingest in homeopathic doses. The high-quality iconography and book design by Gert Dooreman make it a distinguished picture book.

Koenraad Jonckheere, A New History of Western Art – From Antiquity to the Present Day, Hannibal, Veurne, 2022, 472 pages